Personalized hemodynamic resuscitation targeting capillary refill time in early septic shock

Optimal strategy for hemodynamic resuscitation in early septic shock remains uncertain <-> substantial heterogeneity of patients with septic shock which may limit the effectiveness of non personalized resuscitation strategies.

-> recent trials comparing liberal vs restrictive fluid administration or high vs low mean arterial pressure (MAP) targets have failed to improve patient-centered outcomes.

A low diastolic arterial pressure (DAP) reflects decreased vascular tone while a narrow pulse pressure may be associated with a low stroke volume.

Septic shock was defined as suspected or confirmed infection, plus hyperlactatemia (≥ 2.0 mmol/L), and requirement of norepinephrine to maintain a MAP of at least 65 mm Hg after an intravenous fluid load of at least 1000 mL.

Assessment of capillary refill time (CRT) may identify tissue hypoperfusion while its evolution could reflect the progress of resuscitation.

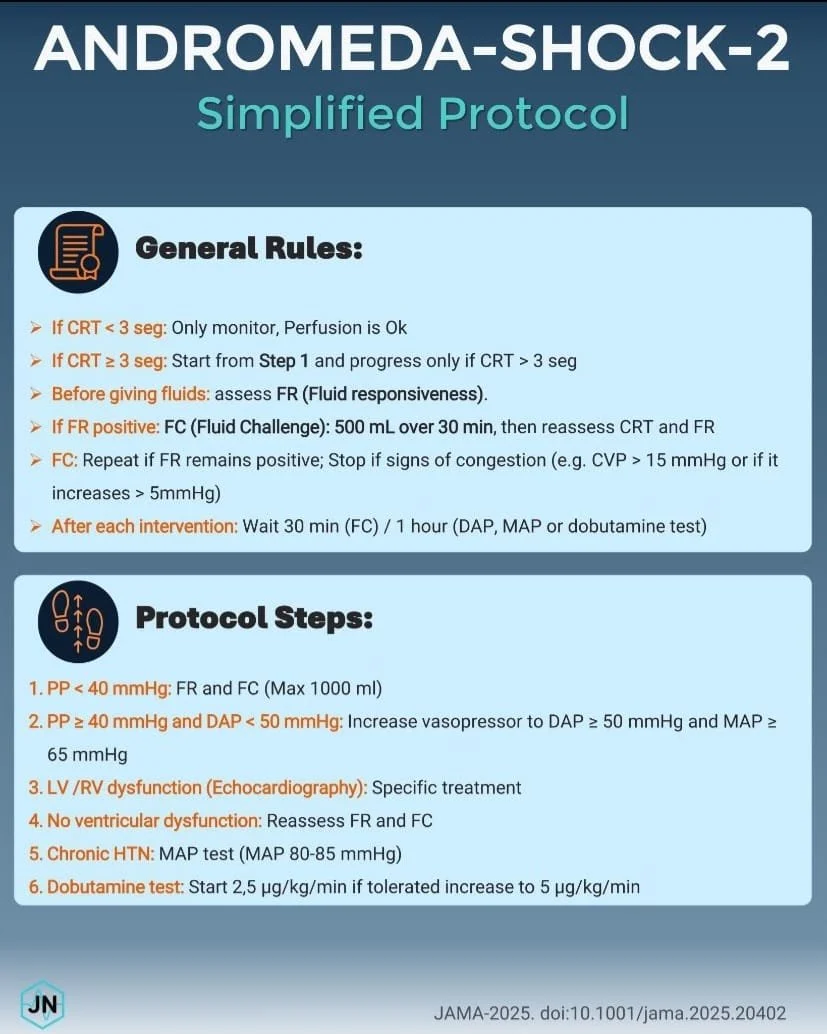

The CRT-PHR (CRT - personalized hemodynamic resuscitation) algorithm was based on 4 fundamental pillars: (1) CRT normalization as the target of hemodynamic resuscitation; (2) baseline identification of individual hemodynamic patterns of cardiovascular dysfunction (persistent hypovolemia, vasoplegia, and cardiac dysfunction) by simple clinical tools (pulse pressure and DAP) and basic bedside echocardiography, followed by specific interventions; (3) systematic fluid-responsiveness assessment before any fluid resuscitation; and (4) 2 acute (1-hour) hemodynamic tests: a trial of a higher MAP target and a trial of a fixed low-dose dobutamine.

CRT was assessed by applying firm pressure to the ventral surface of the distal phalanx for 10 seconds, and then released. A refill time longer than 3 seconds was defined as abnormal.

Patients with abnormal CRT received CRT-PHR implemented in 2 progressive tiers :

Tier 1 started with the evaluation of pulse pressure. In those patients with a pulse pressure less than 40 mm Hg, fluid responsiveness was assessed and in those patients identified as fluid responsive, a 500-mL fluid bolus (of crystalloid or colloid) was administered in 30 minutes and CRT reassessed. If still abnormal, a second fluid bolus was administered in fluid responsive patients. Meanwhile, in those with a pulse pressure of 40 mm Hg or higher and a simultaneous DAP less than 50 mm Hg, norepinephrine was titrated to reach a DAP of 50 mm Hg or higher (DAP adjustment). If these tier 1 interventions failed to normalize CRT, the patient moved to tier 2.

Tier 2 started with basic echocardiography to rule out cardiac dysfunction. In patients with right or left ventricular dysfunction, general treatment recommendations were provided and interventions recorded (right/left ventricular optimization), although no mandatory therapy was part of the CRT-PHR algorithm. If this intervention failed to normalize CRT or cardiac dysfunction was ruled out, fluid responsiveness was reassessed and further fluid boluses were administered in fluid-responsive patients until normalizing CRT, reaching safety limits, or the patient became unresponsive, whichever came first. If the CRT goal was not achieved, a MAP test was performed only in patients who were chronic hypertensive, by transiently increasing norepinephrine to attain a MAP of 80 to 85 mm Hg for 1 hour. If the CRT goal was met, this MAP level was maintained throughout the 6-hour study period. Otherwise, norepinephrine was decreased to the previous dose and the patient moved to a dobutamine test with a fixed low dose (5 μg/kg/min) for 1 hour. Dobutamine was maintained only in those with normalized CRT.

Conclusion :

In this trial including patients with early septic shock, a CRT-PHR strategy was superior to usual care on a hierarchical composite outcome of mortality, duration of vital support, and length of hospital stay at day 28. These results were mainly driven by a shorter duration of vital support.

NB : 9 limitations in this study.

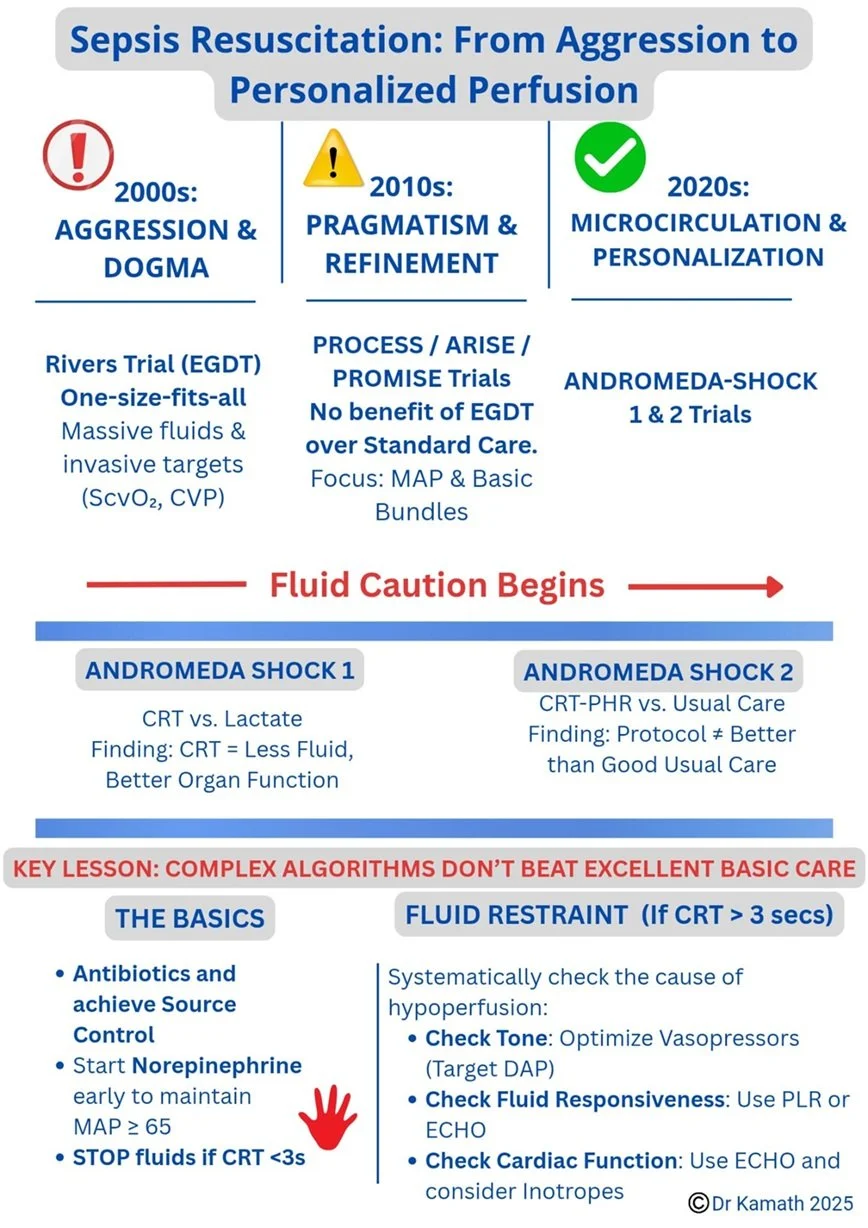

Interesting timeline about this topic by Taranath Kamath.

CRT-guided sequence turned into a pocket #checklist by Jesús Nieves in an attempt to make bedside resuscitation easier, same science and another format.

Personal opinion (F.Caruso) available on X :

Is the main question the mortality reduction ?

Let's imagine the following scenario :

The same patient in septic shock resuscitated using usual care versus personalized therapy (AS-2).

In both cases, the patient survives at 28 days with the same all-cause mortality.

But if the price and path to victory require less hemodynamic support why minimize this result which points toward more personalized and less aggressive medicine ?

Regardless of the issue of 28-day mortality, what can a shorter duration of hemodynamic support and length of hospital stay at day 28 mean for the patient's organs and tissues, his family and the healthcare staff ?

I believe that the work carried out by the AS team is highly relevant and reminds us of the importance of moving away from standardized and non-personalized resuscitation.

By the way let's remember that this team's work (AS-1 and AS-2) helps us on a large scale to distinguish between macro- and microcirculatory aspects, which helps to avoid the over-resuscitation still often encountered in intensive care units (e.g lactate stable or does not decrease > more fluids / vasopressors...).

Thank to the authors AndromedaShock and edu_kattan et al. for your work and contribution.

Frédéric Caruso, M.D